Spinal Muscular Atrophy

- Ruth Wright

- Mar 17, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 15, 2022

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is one of the most common paediatric neuromuscular disorders affecting 1 in 10,000 live births. Untreated, it is a severe and progressive disease associated with reduced life expectancy. Since the first description of SMA in 1891 by Guido Werdnig, there has been immense research conducted to understand the molecular mechanism behind SMA and to develop therapy options (1). This article will aim to describe SMA and its causes and explore the gene therapy options that are out there.

The Clinical Picture

SMA is usually diagnosed in infancy or early childhood but, there are more mild forms which may appear later in life. It is characterised by progressive muscle atrophy and weakness with proximal muscles (e.g. shoulders, hip back) more severely affected compared to more distal muscles. The classical method for disease classification relies on age of onset and disease severity and divides patients into 5 subtypes (SMA type 0-4) (2-3). However, this classification does not consider the dynamic changes observed post treatment. A more practical method for SMA classification groups patients as nonsitters, sitters, and walkers. This places the focus on the functional status of patients and their response to treatment.

Figure 1: Classical and practical classification of SMA (2-6).

SMA type 0 or prenatal SMA is the most rare and severe subtype. Affected infants are often born with join contractures and severe muscle weakness. Due to severe proximal muscle weakness, infants can have severe respiratory insufficiency at birth and often do not survive past a few weeks due to respiratory failure.

SMA type 1 or Werdnig-Hoffmann disease is the most common form of SMA affecting approx. 60% of infants. Affected infants often appear normal at birth but disease onset occurs before the age of 6 months. They are unable to sit independently and usually reach few developmental milestones.

SMA type 2 or Dubowitz disease affects about 30% of infants and usually appears between 6-18 months. As an intermediate form of SMA, children can sit without assistance but as the disease progresses this is usually lost by mid-teens or older. Life expectancy of SMA type 2 is reduced but many reach 25 years old.

SMA type 3 or Kugelberg-Welander disease affects about 13% and appears between early childhood and early adulthood. These individuals are able to walk independently however as the disease progresses this may be lost and individuals may become wheelchair dependent but life expectancy is normal.

SMA type 4 is rare and usually appears after the age of 30. Individuals usually display more mild symptoms and are able to reach all motor miles stones at some point in their lives.

The Molecular Picture

SMA is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by loss of alpha motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord which leads to the characteristic muscle weakness and atrophy. The majority of SMA patients present with a complete deletion of exon 7 and/or 8 of survival motor neuron (SMN1) gene (4). The remaining patients possess SMN1 gene mutations which also inactivate the protein function. There is luckily a backup gene to SMN1, SMN2 which is an analogue of SMN1. SMN2 only produces 10% of the total necessary functional protein therefore the disease severity is determined predominantly by the copy number SNN2.

The SMN genes are located along the same 34kb of chromosome 5 q13 and therefore both contain the same 10 exons (1, 2a, 2b, 3, 4, 5, 6a, 6b, 7, and 8). SMN1 is transcribed from the antisense strand and SMN2 is transcribed from the sense strand. The key difference between the two genes is a transcriptionally silent mutation to exon 7. For SMN1 this mutation is part of an exonic splicing enhancer which allows for SMN1 to be transcribed fully. For SMN2 this mutation is instead an exonic splicing silencer which produces predominantly transcripts which lack exon 7 and only a small portion which correctly include exon 7.

Figure 2: The molecular picture of SMA. The figure to the left illustrates the SMN2 copy number for each SMA type and the figure on the right illustrates the process of transcription for SMN1 and SMN2 mRNA (5).

SMN is an important housekeeping protein which interacts with many proteins and is part of large protein complexes. A reduction in SMN impairs many molecular functions such as splicing, transcription/translation, stress-response, p53-related DNA damage, etc. and play an important role in motor neuron maintenance. Normally individuals have two copies of each SMN1 and SMN2, however the SMN region on 5q13 is highly unstable and as such is prone to unequal recombination and gene conversions leading to copy number variations with some people possessing up to 8 copies of SMN2. For people with SMA, having more copies of SMN2 is associated with reduced disease severity and later onset. However, it should be noted that not all copies of SMN2 are identical and produce the same amount of SMN protein. Typically, SMA type 0 patients have 1 copy of SMN2, type 1 patients have 1-3 copies, type 2 patients have 2-3 copies, type 3 patients have 3-4 copies, and type 4 patients have more than 4 copies (6).

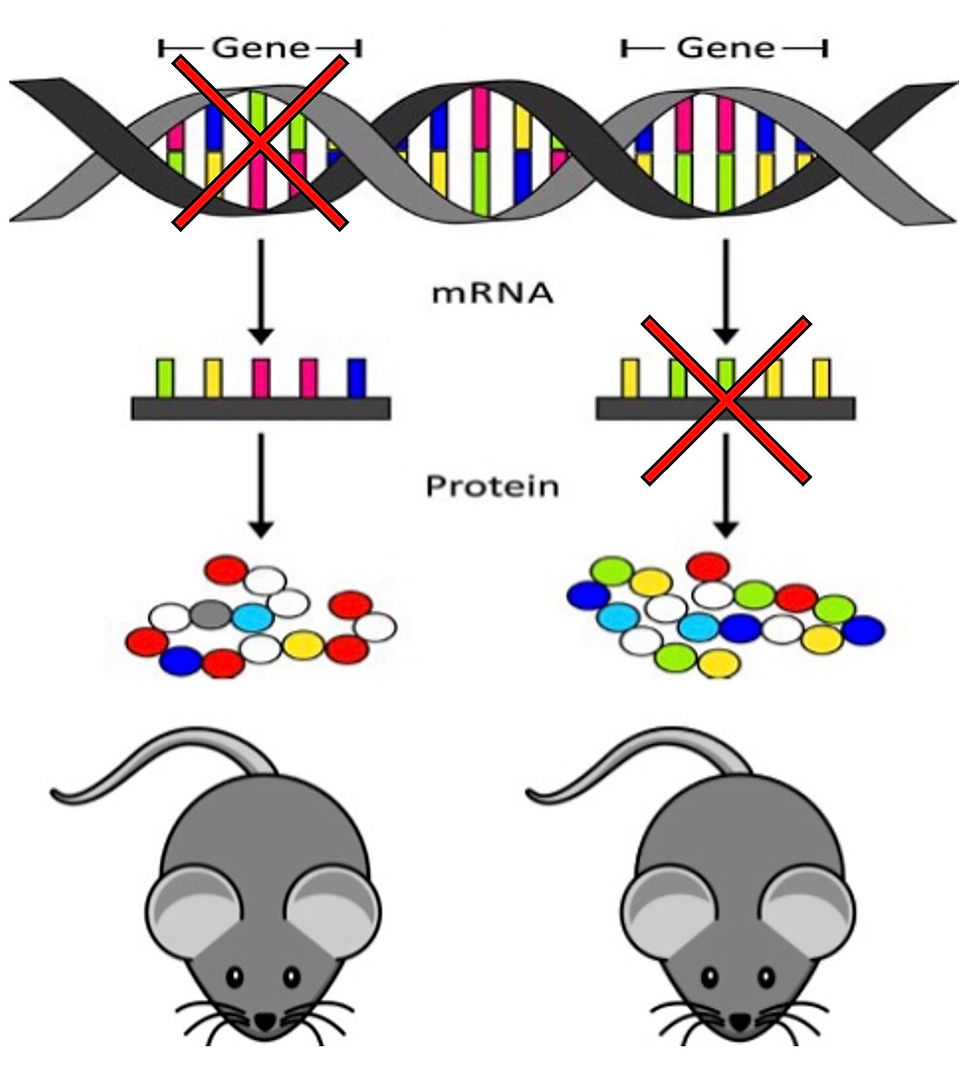

Therapeutic Options

Since linking SMA to SMN1 and SMN2 copy number there have been major advances made in SMN gene targeting therapies. They can be divided into those that modulate SMN2 (Nusinersen/Spinraza and Risdiplam/Evrysdi) and those that target SMN1 for gene replacement (Omasemnogene Abeparvovec-xioi/Zolgensma) (4-5). SMN2 modulating drugs are designed to correct the missplicing of SMN2 and by doing so increase the amount of functional protein produced. Nusinersen does this by binding to ISS-N1 in SMN2 blocking the recruitment of hnRNP-A1 a splicing repressor this promoting exon 7 inclusion. Nusinersen has been found to be safe and well tolerated however, total therapeutic effect is dependent on SMN2 copy number. Risdiplam is a type of small molecules therapy. It corrects SMN2 splicing by facilitating recruitment of U1-snRNP to the splice donor site of intron 7. However, the major dray back of small molecule therapy is the potential risk of off-target effects.

Being a monogenic disorder, SMA offers an excellent opportunity for gene replacement therapy. Omasemnogene Abeparvovec-xioi is an AAV9 vector-based gene therapy which aims to deliver a copy of the SMN1 gene that is able to produce functional SMN protein. The AAV9 vector contains a fully functional human SMN1 transgene. It is capable of crossing the blood brain barrier and doesn’t integrate into the patients’ genome. However, a consequence of the viral capsid is a significant immune response which must be counteracted by glucocorticoid administration. Additionally, the viral load must be considered when administering omasemnogene Abeparvovec-xioi beucase even when the capsid has released the SMN1 transgene to the target cells, the viral capsid remains in the patient's system. As such, patients that are older and therefore heavier in weight, that require a higher dose will also have increased viral load which can surpass the threshold for a manageable immune response. Therefore patients with high AAV9 antibody levels prior to treatment or are above a countries age/weight restriction may be rejected as this would increase the severity of the immune response especially at higher doses.

Figure 3: Current therapeutic options for SMA that target the SMN genes(4-5).

Separate from these SMN targeting therapies there are also several SMN-independent therapy options. Therapies such as those of neuroprotection and restoration of muscle function can be used in a combination to enhance SMN-dependent strategies. However, for all of these therapies to have the best results, patients need to start treatment as early as possible.

Newborn Screening

SMA is a progressive degenerative disease where motor neuron cells are lost and do not regenerate. SMN levels have been shown to be highest prenatally and drastically decrease postnatally, and then drop further after 3 months (5). This corresponds to neuromuscular junction development and emphasize the need for early, preferably pre-symptomatic, intervention for best results. Therefore, newborn screening is vital for pre-symptomatic diagnosis of patients with homozygous SMN1 loss.

Newborn screening is either available or will be available soon in several European countries, US, and Australia (4-5). There are counties such as Isreal that prefer to offer carrier testing to couples to reduce the occurrence of SMA (4-5). However, there are many countries there the cost of therapy is too great to rationalise newborn screening. With SMA therapy costs ranging from $250,000 all the way to $2 million per dose, it is understandable how this is not affordable for many health-care providers (4-5).

Ultimately, available gene therapies for SMA are very impressive and can offer substantial benefits to patients, their families and the wider healthcare system but, at this point the prices are not sustainable.

References

Werdnig, G. (1891). Zwei frühinfantile hereditäre Fälle von progressiver Muskelatrophie unter dem Bilde der Dystrophie, aber anf neurotischer Grundlage. Archiv Für Psychiatrie Und Nervenkrankheiten, 22(2), 437-480. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01776636.

Conditions, G. (2022). Spinal muscular atrophy: MedlinePlus Genetics. Medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 17 March 2022, from https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/spinal-muscular-atrophy/.

Spinal Muscular Atrophy - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). (2022). Retrieved 17 March 2022, from https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/spinal-muscular-atrophy/.

Wirth, B. (2021). Spinal Muscular Atrophy: In the Challenge Lies a Solution. Trends In Neurosciences, 44(4), 306-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2020.11.009

Wirth, B., Karakaya, M., Kye, M., & Mendoza-Ferreira, N. (2020). Twenty-Five Years of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Research: From Phenotype to Genotype to Therapy, and What Comes Next. Annual Review Of Genomics And Human Genetics, 21(1), 231-261. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-102319-103602

Lopez‐Lopez, D., Loucera, C., Carmona, R., Aquino, V., Salgado, J., & Pasalodos, S. et al. (2020). SMN1 copy‐number and sequence variant analysis from next‐generation sequencing data. Human Mutation, 41(12), 2073-2077. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.24120

Comments